Today’s article is a first for Yopp: We have our very first interview! The wonderful Dennis Upkins had the opportunity to connect with Alice Wong, an amazing disability activist who I’ve admired from afar for several years, about the importance of the stories of disabled people. If you’ve been looking for some disability related resources to consume and activists to follow, this article is full of them. I highly recommend going and checking out Alice’s work once you’ve finished reading here.

CN: general discussion of disability, and ableism; brief discussion of racism, chronic illness, the pandemic, and eugenics

One of the true joys of my career is that I get to meet some truly extraordinary and amazing people from all walks of life. These individuals are using their gifts to make this world a better one. A few of them, I’m both honored and humbled to consider colleagues and good personal friends.

Case in point: Alice Wong.

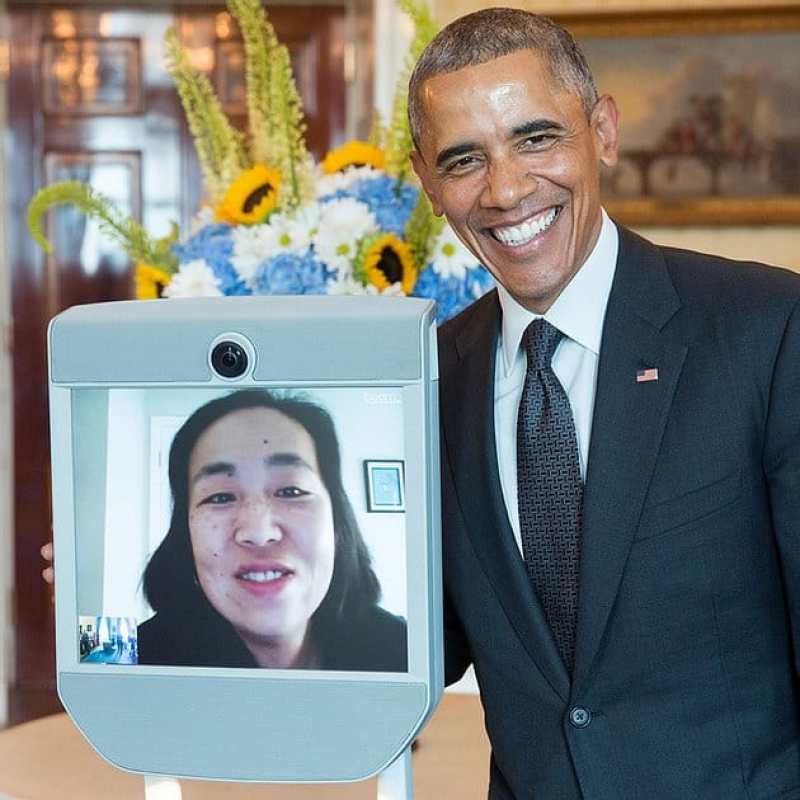

Activist, media consultant, founder of the Disability Visibility Project, and excellence personified, Alice and I first crossed paths during our time as contributors for The Nerds of Color, a few years ago. I’ve learned a lot from Alice. Not only in regards to disability issues, but also in terms of being a leader, a class act, and showing true solidarity with other marginalized groups. If you don’t believe me, you can always ask President Obama. In 2013 he appointed Alice to the National Council on Disability.

This year alone has been a milestone for Ms. Wong. She recently released a new book entitled Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century which is available now and appeared on the cover of British Vogue.

I recently got the opportunity to catch up with Alice and discuss everything ranging from the new book, her podcast, activism, to the power of storytelling.

Upkins: Alice thank you so much for taking the time to do this interview. For those who are unfamiliar, share a bit of background about yourself.

Wong: Thanks Denny–always fun to be talking with a fellow nerd!! I’m the Founder and Director of the Disability Visibility Project, an online community dedicated to creating, sharing, and amplifying disability media and culture. I started it in 2014 as a one-year oral history campaign to record stories by disabled people for the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and it snowballed into a bigger thing. I have a podcast and blog, I published guest essays, and I edited and published #ADA30InColor, a series of essays by disabled people of color this past July for the 30th anniversary of the ADA. As a side hustle, I’m a research consultant. I also have a new book that just came out, Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century, available now from Vintage Books.

Upkins: For some, activism is what they do, for others it’s a part of who they are. How did you find your calling?

Wong: It took me a long time to be comfortable identifying as an activist. As a person born disabled in a world that was never built for me, I had no choice to be an activist as a means of survival. I had to advocate for myself and I didn’t see it from a larger social and political and social perspective until I was a young adult. Even then, as I became involved in the disability community in the San Francisco Bay Area I didn’t do it as my ‘job,’ it was an act of love and service. For the last 5-6 years, most of my activism takes place in my writing, media making, and through social media. People described me as a community organizer and I still wonder if that’s accurate because I’ve internalized the idea of an activist or organizer as someone who is doing things ‘on the ground.’ Over time I’m becoming more ok with it because I believe what I do is activism and that we need to expand our ideas of who gets to be an activist and what activism looks like.

Upkins: The Disability Visibility Project, how did that idea become a reality?

Wong: The initial idea came from my frustration at the lack of disability history, especially stories of current disability history and stories by actual disabled people. The DVP first started as a community partnership with StoryCorps, an oral history nonprofit, where I encouraged disabled people to come in (or use their app) to record a story. StoryCorps has an arrangement with the Library of Congress giving participants an option of archiving it there for the public which is incredibly cool–we can create our own history and leave it there for generations. As of 2020, we recorded approximately 140 oral histories since 2014 and that makes me feel good. I made it a reality by creating a website and using social media to spread the word. And it was thanks to the community who supported it enthusiastically.

Upkins: In recent years Selma Blair garnered headlines when she disclosed having multiple sclerosis. In many ways, she became a face for disability advocacy. This point was explored in the book with Zipporah Arielle’s essay, Selma Blair Became a Disabled Icon Overnight. Here’s Why We Need More Stories Like Hers. Who are other significant activists and trailblazers in the disability movement who may not be as famous as Ms. Blair?

Wong: So many people!! There are so many badass disabled people changing the game. Here are just a few:

Andraéa LaVant, Impact Producer for Netflix’s Crip Camp and President of LaVant Consulting, Inc. I recently interviewed Andraéa about her work on the impact campaign for the latest issue of Break the Story, an online publication from the Pop Culture Collaborative.

Vilissa K. Thompson, LMSW, a disability rights consultant, writer, activist from Winnsboro, SC, and the creator of #DisabilityTooWhite.

Rebecca Cokley, Director of the Disability Justice Initiative at the Center for American Progress who has been instrumental in advancing disability issues in the last several Presidential elections.

Upkins: What are some major misconceptions and beliefs regarding disability issues that you find yourself debunking most often?

Wong: There’s a lot and the bar is so low. I find myself repeating some of the most basic things but unfortunately, this is where we are. A few things I try to change regarding narratives and beliefs about disability:

- Disabled lives are not worth living.

- Disabled lives are filled with suffering, tragedy, or bitterness.

- Disabled people ‘take’ and consume rather than offer rich insights, creativity, and innovation to the world.

- The future is one where disability, pain, and suffering do not exist.

Upkins: For parents who may learn that their child may be disabled and have challenges ahead of them, what advice would you give them in terms of navigating the unknown and being the best parents they can be for their child?

Wong: My parents told me they cried when they found out about my diagnosis. The shock and sadness is real. However, I was still their kid and they expected the same things from me as with my younger sisters, if not more since I was the oldest. I hope they will center their child on what they are experiencing and giving them a space to be angry, non-compliant, and frustrated. I hope they will seek out advice from disabled adults from the community and learn about the possibilities their child can have. I hope they will also rely on their own intuition and feel empowered to not heed every single piece of advice from professionals who frankly don’t know everything and cannot predict the future.

Upkins: One thing you have reiterated over the years on social media as well as in the introduction of the new book is the power of storytelling and the profound impact it can have. Would you mind expounding on this idea for readers?

Wong: Books were a gateway to freedom for me. I felt free and believe that everyone deserves to be seen and heard in books and all forms of culture and media. Stories can give a glimpse of what’s beyond our individual situations and this is incredibly powerful for people who receive messages from society that they are not enough or that they don’t count.

Upkins: I remember a little over a year ago, you reached out to me because two very talented Black writers were attempting to share their truths about the anti-blackness Lupita Nyong’o endured for starring in Us and the white privilege of Netflix’s Special respectively. Both writers got backlash for speaking truth to power. Nevertheless, you wanted to make certain their voices were heard. For PoCs with disabilities, how much of a fight is it to simply be heard?

Wong: It’s tough because let’s face it, racism, antiblackness, sexism, homophobia is real and no community is immune from them. I am always interested in dissenting or different takes from the media hype around things, especially from disabled perspectives. When I see Asian American or disability representation in films or tv I also notice a pressure to have to embrace it without critique because of how little exists. We deserve more than the crumbs and we also need space for nuanced perspectives. People can read the two essays, by Da’Shaun Harrison and D’Arcee Charington Neal. I also recommend this fantastic essay for the DVP by Vyoma Raman on the Netflix series Never Have I Ever.

Upkins: Covid-19. It’s been a paradigm shift of sorts on a global scale. In your estimation, has the pandemic brought focus and resources to those with special needs or did it do the opposite?

Wong: First off, let’s abolish the term ‘special needs.’ Seriously, in 2020, we can eschew euphemisms and be more precise on who and what we’re talking about–disability. I feel great ambivalence about what’s happened during the pandemic. Suddenly, as non-disabled people were inconvenienced and had things taken away from them, access miraculously became available despite decades of advocacy by disabled people for accessible classes, remote working, and online conferences, performances, and events. During this same period, we’ve seen a narrowing of access and services for sick, disabled, and immunocompromised people. The rhetoric around ‘high risk’ people as acceptable losses is straight-up eugenic and this clearly also applies to Black, brown, and indigenous communities. I am glad to finally see people realizing what systemic racism and ableism looks like in the ways that our lives are devalued and deprioritized when it comes to testing and treatment for COVID-19. This year I wrote about the shortages of ventilators and health care rationing and the invisibility of deaths in congregant settings.

Upkins: Disability Visibility: First Person StoriesFrom the 21st Century. How did this anthology come about?

Wong: Catherine Tung, an editor at Vintage Books at the time, emailed me in 2018 about whether I had an interest in editing an anthology and I told her YES and that I had a great idea for it. After several conversations, I was able to prepare a book proposal and find an agent to submit it. I am very grateful for this opportunity and had an excellent experience working with the people at Vintage.

Upkins: How were each of the authors selected? Have you previously collaborated with any of them?

Wong: In preparation for the anthology I created a spreadsheet of stories I loved over the last 20 years and it was a matter of deciding what kinds of stories and being intentional about the kinds of people I wanted to highlight. Each piece is unique, personal, and powerful. There were many more I wanted to include and I have a section in the back with a list of additional reading for people to explore.

Upkins: Disability Visibility: First Person Stories From the 21st Century. I didn’t know what to expect when I began reading and instantly I was blown away. Each piece was textured and nuanced. Was this organic, by design, or a combination of the two?

Wong: Yes–this was all part of the master plan *evil laugh*. I wanted to challenge readers with work that’s substantive, not Disability 101 or aimed to garner awareness or empathy. I also wanted to show just a small sample of the brilliance of disabled people doing a wide range of things. These contributors all have something to say and putting them together side-by-side was strategic. There are heavier, serious pieces, there are lighter pieces. Some are long while others are short and there is a wide range of writing styles which is important to me. There is a free plain language version of Disability Visibility and a discussion guide on my website if people are interested. Both are written by disabled writers, Sara Luterman and Naomi Ortiz respectively.

Upkins: As a reader, I found there was a component I could connect with in nearly every story. For example, being Indigenous myself, Jen Deerinwater’s (The Erasure of Indigenous People In Chronic Illness) firsthand account of invisibility and erasure was all too familiar. Jeremy Woody’s plight (The Isolation of Being Death In Prison) broke my heart. When Keah Brown explained (Nurturing Black Disabled Joy) that discovering joy as a queer disabled Black woman incites rage, hatred, and backlash from others, that resonated with me on too many levels. Were these universal elements something you noted while editing the book?

Wong: Not exactly–I don’t expect people to identify with every piece but I hope there is something for everyone. I also hope that one does not need to connect to something personally in order for them to appreciate and understand it. This is the opportunity and potential–to share something unexpected and revelatory without preaching.

Upkins: A point that was reiterated in many of the pieces is that these individuals aren’t waiting to be “fixed” or “healed.” In an ableist culture, why can’t this be stressed enough?

Wong: Just the other day the asswipe known as Elon Musk was touting a brain implant that according to him would ‘fix’ all kinds of disabilities. People eat this shit up because it’s edgy and futuristic. People forget that it’s also hella eugenic and ableist. And ableism is always bound up with white supremacy and heteropatriarchy, so there’s that. The struggle (and work) never ends but if more non-disabled people after reading the book get it and decide to push back on these kinds of ‘progress,’ it would be one of many ways to be in solidarity with us.

Upkins: What’s been the reception and feedback to the anthology thus far?

Wong: Pretty good! It’s a weird time to come out with a book but I think it’s giving people a lot of joy and comfort. I also think there’s a hunger for a book like this in the world for both disabled and non-disabled people. I am always blown away by seeing people post selfies with the book or sharing their responses online. One cool thing that I cannot get over is the fact that Disability Visibility was selected for the Noname Book Club this September! I died, let me tell you, DIED!

Upkins: You recently appeared on the cover of British Vogue. Congratulations. That had to be exciting and surreal for you?

Wong: Quite surreal for sure! An editor reached out to ask for a photo and I figured it was for an article but either I forgot or didn’t realize it would be on the cover. I definitely felt like the odd one out in that group of esteemed activists!

Upkins: You and I initially met during our time on the Nerds of Color? In keeping with the power of storytelling, what fandoms and speculative media are your personal favorites? Which characters and stories were influential on your journey in becoming the individual I’m interviewing now?

Wong: Gotta love the Nerds of Color! Shout-out to Keith Chow who invited me to be part of the crew and write for the blog. My go-to fandoms are Star Trek (DS9, TNG, Voyager, Discovery in that order) and X-Men. I am looking forward to the new version of Dune because I loved the books as a teenager and am intrigued by it especially since the director, Denis Villeneuve, did a remarkable job with Blade Runner 2049 (Blade Runner is one of my all-time favorite movies).

Upkins: So aside from promoting the book, what lies ahead for Alice Wong in the immediate future?

Wong: I have a few things in the works that I can’t reveal just yet. I am continuing with my podcast, publishing guest essays periodically, and continuing my activism with #CripTheVote on Twitter in the lead up to Election Day. #CripTheVote is an online movement encouraging the political participation of disabled people with my co-partners Gregg Beratan and Andrew Pulrang.

Upkins: Where can readers grab a copy of Disability Visibility: First Person Stories From the 21st Century?

Wong: Folks can find my book in paperback, audiobook, and e-book from major retailers by going to the publisher’s website. My website also has info on upcoming book events, media coverage, and other goodies about the book.

Upkins: Where can someone follow you and the Disability Visibility Project?

Wong: On Twitter, I’m @SFdirewolf and @DisVisibility. I can be found on Instagram: @disability_visibility and my website is disabilityvisibilityproject.com.

About the guest blogger/interviewer: Dennis R. Upkins is a speculative fiction author, a journalist, and an equal rights activist. His first two young adult novels, Hollowstone and West of Sunset, were released through Parker Publishing. Both Upkins and his previous work have been featured in Harvard Political Law, Bitch Media, MTV News, Mental Health Matters, The Nerds of Color, Black Girl Nerds, Geeks OUT, Black Power: The Superhero Anthology, Sniplits, The Connect Magazine, and 30Up. You can learn more about him at his website dennisupkins.wordpress.com.